Viva Zapata! Mexican Revolutionary hero Emiliano Zapata poses in full war regalia. This old picture is a classic of the Revolution, with Zapata clutching a Winchester rifle and wearing the obligatory crossed bandoliers and broad sombrero. Last week was the 99th anniversary of the Mexican Revolution, which erupted on November 20, 1910. I had already collected a number of these wonderful old photos for a magazine article I wrote, and I decided to pair them up with some of the photos I shot at the Revolution Day celebration in Ajijic. The commentary that follows will focus both on the past and the present.

Viva Zapata! Mexican Revolutionary hero Emiliano Zapata poses in full war regalia. This old picture is a classic of the Revolution, with Zapata clutching a Winchester rifle and wearing the obligatory crossed bandoliers and broad sombrero. Last week was the 99th anniversary of the Mexican Revolution, which erupted on November 20, 1910. I had already collected a number of these wonderful old photos for a magazine article I wrote, and I decided to pair them up with some of the photos I shot at the Revolution Day celebration in Ajijic. The commentary that follows will focus both on the past and the present.Emiliano Zapata was one of the two great generals of the Revolution who rose from humble places among the people. He was born on a small rancho in Morelos State, south of Mexico city. At an early age, he started organizing the campesinos against illegal land seizures by the hacienda owners. When the Revolution started, he was already leading an armed struggle for Tierra y Libertad (Land and Liberty).

Solemn and martial, a young Ajijic boy marched in Revolution Day parade. Parents take great pride in dressing up their kids for this colorful parade. In pre-Revolutionary days, a boy like this would have had little chance for education or advancement in life. He might have spent his life as a near-serf on a hacienda, or working in a mine or factory and owing the company store more than he could ever repay. His son would inherit the debt and be forced to work in his place after the father's death. Today, a child like this has access to an education up to the university level, health care, the minimum wage and other worker rights, including the right to work wherever he wants. This is not to say Mexico doesn't still have deep social and economic problems, and poverty on a large scale, but this boy has much better opportunities in life than his pre-Revolutionary ancestors.

Solemn and martial, a young Ajijic boy marched in Revolution Day parade. Parents take great pride in dressing up their kids for this colorful parade. In pre-Revolutionary days, a boy like this would have had little chance for education or advancement in life. He might have spent his life as a near-serf on a hacienda, or working in a mine or factory and owing the company store more than he could ever repay. His son would inherit the debt and be forced to work in his place after the father's death. Today, a child like this has access to an education up to the university level, health care, the minimum wage and other worker rights, including the right to work wherever he wants. This is not to say Mexico doesn't still have deep social and economic problems, and poverty on a large scale, but this boy has much better opportunities in life than his pre-Revolutionary ancestors. Soldados y Adelitas. For all of Mexico's macho reputation, there was a time when women fought fiercely alongside the male soldiers. Although they originally followed their men to war to cook their food and take care of the wounded, women soon picked up weapons and became valued warriors in the field. A corrido, (ballad) called "Adelita" became popular when it was sung around the army campfires. It recalled a young woman named Adelita who went to war with her soldier boyfriend. Ever after, these women soldiers were called Las Adelitas. In addition to the two young women in the front row, notice the soldier with the violin behind them, probably even then thinking up a new corrido. The inscription on the lower left says Tuesday, 23 of April, 1912 and further information suggests that these were part of Zapata's army.

Soldados y Adelitas. For all of Mexico's macho reputation, there was a time when women fought fiercely alongside the male soldiers. Although they originally followed their men to war to cook their food and take care of the wounded, women soon picked up weapons and became valued warriors in the field. A corrido, (ballad) called "Adelita" became popular when it was sung around the army campfires. It recalled a young woman named Adelita who went to war with her soldier boyfriend. Ever after, these women soldiers were called Las Adelitas. In addition to the two young women in the front row, notice the soldier with the violin behind them, probably even then thinking up a new corrido. The inscription on the lower left says Tuesday, 23 of April, 1912 and further information suggests that these were part of Zapata's army. Modern-day soldados and Adelitas. Children in period costume march down Hidalgo street toward the plaza. Although there is still much that is macho in Mexican culture, women pursue most of the occupations that men do, particularly at the professional level. All three of the immigration attornies we have used are women, as are most of the dentists we have tried.

Modern-day soldados and Adelitas. Children in period costume march down Hidalgo street toward the plaza. Although there is still much that is macho in Mexican culture, women pursue most of the occupations that men do, particularly at the professional level. All three of the immigration attornies we have used are women, as are most of the dentists we have tried.President Porfirio Diaz, pompous and medel-bedecked. I found this old photo of Porfirio Diaz, the dictator who held power for nearly 30 years before he was overthrown by revolutionary troops under Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. Mexico advanced economically under Diaz, with new factories, oil fields, and thousands of miles of railroad. However, the fruits of this development flowed overwhelmingly to a small segment at the top of society, and to foreign corporations who dominated most of the key industries. Diaz maintained control through police-state tactics and rigged elections.

Ajijic parade shows off Porfiristas as well as Revolutionaries. The little girl above seems thrilled to be dressed in such finery. The little boy bears a remarkable resemblence to Porfirio Diaz in the previous picture. Under the "Porfiriate" there was a vast gap between the wealthy and the poor. The wealthy maintained their positions through debt laws, company stores, illegal land seizures, brutal repression of strikes and other such tactics. The greater the repression, the more resentment built, waiting only for a spark to ignite rebellion.

Ajijic parade shows off Porfiristas as well as Revolutionaries. The little girl above seems thrilled to be dressed in such finery. The little boy bears a remarkable resemblence to Porfirio Diaz in the previous picture. Under the "Porfiriate" there was a vast gap between the wealthy and the poor. The wealthy maintained their positions through debt laws, company stores, illegal land seizures, brutal repression of strikes and other such tactics. The greater the repression, the more resentment built, waiting only for a spark to ignite rebellion. Pancho Villa was a bandit before he became a general. Villa grew up as a sharecropper in the northern state of Chihuahua. He experienced the arrogance and brutality found on some haciendas when one of the haciendados (ranch owners) raped his sister. After tracking the man down, he killed him, stole his horse, and fled to the mountains of Chihuahua for the life of a bandit. An aide to revolutionary leader Francisco Madero tracked him down and persuaded him to put the leadership skills he had developed as a bandit chieftain at the service of the Revolution. Madero's call for rebellion against Diaz was the spark that set off the Revolution. Villa was one of the key leaders who helped win it.

Pancho Villa was a bandit before he became a general. Villa grew up as a sharecropper in the northern state of Chihuahua. He experienced the arrogance and brutality found on some haciendas when one of the haciendados (ranch owners) raped his sister. After tracking the man down, he killed him, stole his horse, and fled to the mountains of Chihuahua for the life of a bandit. An aide to revolutionary leader Francisco Madero tracked him down and persuaded him to put the leadership skills he had developed as a bandit chieftain at the service of the Revolution. Madero's call for rebellion against Diaz was the spark that set off the Revolution. Villa was one of the key leaders who helped win it. Pancho Villa rides again! A handsome young charro (cowboy) guides his horse skillfully through the crowd. This fellow's boots didn't near reach the stirrups, but he had full control of his mount. Ranch kids learn to ride literally almost before they can walk. I am often amazed to see a 700 lb. horse obediently taking direction from a 40 lb rider. The charro outfit, tooled saddle, and fine horse indicate this young charro has a fairly well-to-do father. Although Zapata and Villa were from the lower classes, many wealthier people supported the Revolution, particularly in the early stages. Porfirio Diaz' dictatorship shut out many talented and well-to-do people from leadership positions they felt they deserved.

Pancho Villa rides again! A handsome young charro (cowboy) guides his horse skillfully through the crowd. This fellow's boots didn't near reach the stirrups, but he had full control of his mount. Ranch kids learn to ride literally almost before they can walk. I am often amazed to see a 700 lb. horse obediently taking direction from a 40 lb rider. The charro outfit, tooled saddle, and fine horse indicate this young charro has a fairly well-to-do father. Although Zapata and Villa were from the lower classes, many wealthier people supported the Revolution, particularly in the early stages. Porfirio Diaz' dictatorship shut out many talented and well-to-do people from leadership positions they felt they deserved. Tough-looking troopers surround their chief. It was typical of Villa to wear the casual dress of his soldiers when he was in the field. I imagine it was one of the things they loved about their rough-and-ready leader. Here, he stands in the center of a heavily armed group adorned with the huge sombreros favored by the peasant armies of Villa and Zapata. Although they weren't as well-dressed as Diaz' federalistas, Villa's soldiers won most of their early battles, making up in bravery and revolutionary ardor for their sartorial deficiencies. Most of the rifles here appear to be German Mausers, the rifle of choice for all sides in the war, when they could get them. Its deadly qualities would soon be experienced by Allied soldiers on the battlefields of World War I Europe.

Tough-looking troopers surround their chief. It was typical of Villa to wear the casual dress of his soldiers when he was in the field. I imagine it was one of the things they loved about their rough-and-ready leader. Here, he stands in the center of a heavily armed group adorned with the huge sombreros favored by the peasant armies of Villa and Zapata. Although they weren't as well-dressed as Diaz' federalistas, Villa's soldiers won most of their early battles, making up in bravery and revolutionary ardor for their sartorial deficiencies. Most of the rifles here appear to be German Mausers, the rifle of choice for all sides in the war, when they could get them. Its deadly qualities would soon be experienced by Allied soldiers on the battlefields of World War I Europe. A rather more easy-going group of soldados. Kids in the Ajijic parade joke and poke one another, as young boys will do in any situation. Boys this age sometimes accompanied their fathers or older relatives into the army, and sometimes saw action. Kids grew up very young during the Revolution.

A rather more easy-going group of soldados. Kids in the Ajijic parade joke and poke one another, as young boys will do in any situation. Boys this age sometimes accompanied their fathers or older relatives into the army, and sometimes saw action. Kids grew up very young during the Revolution. Villa poses with one of his many wives. Pancho Villa was reputed to have married 26 different women. There was no information with the picture indicating which one this was. Where he found the time to be married at all is a mystery to me. The Revolution kept him pretty busy for nearly 10 years.

Villa poses with one of his many wives. Pancho Villa was reputed to have married 26 different women. There was no information with the picture indicating which one this was. Where he found the time to be married at all is a mystery to me. The Revolution kept him pretty busy for nearly 10 years. Young love in the modern day. This pretty young girl seems to have a firm grasp on her escort for the parade. She is dressed in a beautifully woven skirt, an embroidered top and the obligatory rebozo tied across her chest. She seems to be contemplating her next move in the relationship. A typical male, he hasn't a clue what's up.

Young love in the modern day. This pretty young girl seems to have a firm grasp on her escort for the parade. She is dressed in a beautifully woven skirt, an embroidered top and the obligatory rebozo tied across her chest. She seems to be contemplating her next move in the relationship. A typical male, he hasn't a clue what's up. Pancho Villa rides with his army toward the border town of Ojinaga. After he seized Chihuahua, a substantial number of federalistas retreated north to Ojinaga, a town just across the Rio Grande from Presidio, Texas. Not wanting to leave this force behind him when he turned south toward Mexico City, Villa led his army to a resounding victory at Ojinaga. The battle sent many of the federalistas fleeing across the border into Texas to be interned by the US Army. They were among the first of a massive wave of Mexicans who crossed the border to escape the horrors of a war that cost the lives of as many as 1 out of 7 Mexicans. This is my favorite photo of Pancho Villa. He is completely unposed, dressed in his usual slovenly fashion when in the field, and is seen here demonstrating the superior horsemanship he developed as a bandit raider.

Pancho Villa rides with his army toward the border town of Ojinaga. After he seized Chihuahua, a substantial number of federalistas retreated north to Ojinaga, a town just across the Rio Grande from Presidio, Texas. Not wanting to leave this force behind him when he turned south toward Mexico City, Villa led his army to a resounding victory at Ojinaga. The battle sent many of the federalistas fleeing across the border into Texas to be interned by the US Army. They were among the first of a massive wave of Mexicans who crossed the border to escape the horrors of a war that cost the lives of as many as 1 out of 7 Mexicans. This is my favorite photo of Pancho Villa. He is completely unposed, dressed in his usual slovenly fashion when in the field, and is seen here demonstrating the superior horsemanship he developed as a bandit raider. Mexican horsemanship didn't die with Pancho Villa. A charro dances his horse in time with a blaring brass band in the Ajijci Plaza. A fellow charro and spectators grin with appreciation at his skill. To see these highly trained horses dancing along the cobblestone streets is an amazing spectacle. The Charro Tradition began in Jalisco State, where I live.

Mexican horsemanship didn't die with Pancho Villa. A charro dances his horse in time with a blaring brass band in the Ajijci Plaza. A fellow charro and spectators grin with appreciation at his skill. To see these highly trained horses dancing along the cobblestone streets is an amazing spectacle. The Charro Tradition began in Jalisco State, where I live. Villa and Zapata enter Mexico city together, at the head of their troops. Pancho Villa is in the center of the second rank for horsemen. As it was a formal occasion, Villa wore a uniform. Just to the left of Villa, in the large sombrero, is Emiliano Zapata. Their armies jointly marched into the city, after ousting their enemy Carranza. Zapata's troops were disciplined, and city residents were amazed when they politely knocked on doors and asked for food. Villa's troops were as unruly as their bandit chieftain-turned general, and eventually Villa had to pull out of the city because of citizen complaints.

Villa and Zapata enter Mexico city together, at the head of their troops. Pancho Villa is in the center of the second rank for horsemen. As it was a formal occasion, Villa wore a uniform. Just to the left of Villa, in the large sombrero, is Emiliano Zapata. Their armies jointly marched into the city, after ousting their enemy Carranza. Zapata's troops were disciplined, and city residents were amazed when they politely knocked on doors and asked for food. Villa's troops were as unruly as their bandit chieftain-turned general, and eventually Villa had to pull out of the city because of citizen complaints. Charros canter down the street with the same esprit as the old revolutionary army. With a few bandoliers and Winchesters, they could have stepped right out of history. Charros are well organized and trained and take great pride in their traditions and skills.

Charros canter down the street with the same esprit as the old revolutionary army. With a few bandoliers and Winchesters, they could have stepped right out of history. Charros are well organized and trained and take great pride in their traditions and skills.  Ready to sing or fight. This squad of revolutionary soldados is armed to the teeth with guns and musical instruments. The old man with the violin and the boy with the guitar probably accompanied them on many a corrido around the campfire. There are at least two types of corridos: epic and narrative. The epic corrido carries a tradition that goes back to the ancient Greece of Homer and the Viking sagas. It tells the stories of great heros and their deeds. The narrative tells of notable events such as train wrecks and great love affairs. The lyric quality of the corrido distinguishes it from other traditions. It is the voice of the people sung from the heart and accompanied, usually, by the guitar. Corridos are a musical art form still practiced today.

Ready to sing or fight. This squad of revolutionary soldados is armed to the teeth with guns and musical instruments. The old man with the violin and the boy with the guitar probably accompanied them on many a corrido around the campfire. There are at least two types of corridos: epic and narrative. The epic corrido carries a tradition that goes back to the ancient Greece of Homer and the Viking sagas. It tells the stories of great heros and their deeds. The narrative tells of notable events such as train wrecks and great love affairs. The lyric quality of the corrido distinguishes it from other traditions. It is the voice of the people sung from the heart and accompanied, usually, by the guitar. Corridos are a musical art form still practiced today. "La Cucaracha, la cucaracha..." This little boy belted out the famous marching corrido of Pancho Villa's Division of the North. This corrido, or at least its title, is probably one of the few Mexican songs familiar to most norteamericanos. It bemoans the cockroaches of army camp life, the lack of marijuana to smoke, and the desire to braid the beard of Venustiano Carranza, an enemy of Villa, into a hat band for their bandit-general. A corrido has potentially endless verses, limited only by the imagination (and probably the tequila supply) of the singer.

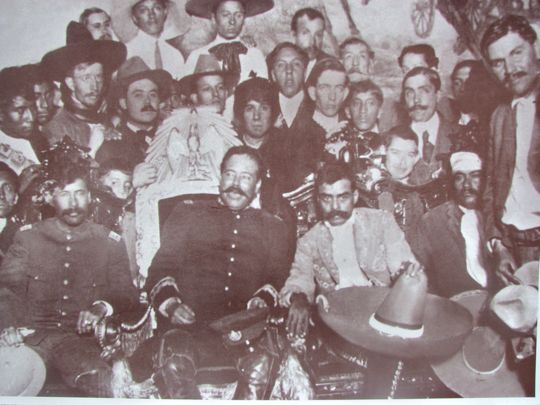

"La Cucaracha, la cucaracha..." This little boy belted out the famous marching corrido of Pancho Villa's Division of the North. This corrido, or at least its title, is probably one of the few Mexican songs familiar to most norteamericanos. It bemoans the cockroaches of army camp life, the lack of marijuana to smoke, and the desire to braid the beard of Venustiano Carranza, an enemy of Villa, into a hat band for their bandit-general. A corrido has potentially endless verses, limited only by the imagination (and probably the tequila supply) of the singer. High tide for the people's Revolution. Villa (left center), and Zapata (right center) sit together in the National Palace in Mexico City after forcing their former ally Venustiano Carranza to flee. Carranza had refused to acknowledge the presidential choice of a convention of revolutionaries, wanting the job for himself. To me, this picture captures the different personalities of the two generals. Villa is ebullient and jocular. Zapata is brooding and a little dreamy. His Plan of Ayala was not only visionary but he put it into practical application with such effectiveness that US President Wilson's emissary declared the Zapata-controlled territory as an area of "true social revolution". Villa never quite got away from his bandit background, and had a habit of funding his revolutionary army with bank and train robberies and by kidnapping haciendados. He endorsed the Plan of Ayala but never produced anything comparable for the areas he controlled. Ultimately, both revolutionaries were assassinated by their enemies, Zapata in 1917 and Villa in 1923. After they died, revolutionary leaders of a more elite background assumed control, and although these new leaders implemented important reforms, the kind of social revolution envisioned by Zapata and endorsed by Villa died with them.

High tide for the people's Revolution. Villa (left center), and Zapata (right center) sit together in the National Palace in Mexico City after forcing their former ally Venustiano Carranza to flee. Carranza had refused to acknowledge the presidential choice of a convention of revolutionaries, wanting the job for himself. To me, this picture captures the different personalities of the two generals. Villa is ebullient and jocular. Zapata is brooding and a little dreamy. His Plan of Ayala was not only visionary but he put it into practical application with such effectiveness that US President Wilson's emissary declared the Zapata-controlled territory as an area of "true social revolution". Villa never quite got away from his bandit background, and had a habit of funding his revolutionary army with bank and train robberies and by kidnapping haciendados. He endorsed the Plan of Ayala but never produced anything comparable for the areas he controlled. Ultimately, both revolutionaries were assassinated by their enemies, Zapata in 1917 and Villa in 1923. After they died, revolutionary leaders of a more elite background assumed control, and although these new leaders implemented important reforms, the kind of social revolution envisioned by Zapata and endorsed by Villa died with them. The future of Mexico. Two little girls peer out of a second floor window, near where I had set up on the roof of the Secret Garden restaurant so I could get overhead shots of the parade. Mexico's children are its future, and it must have a big future because it has so many. These two were darling and immediately wanted me to take their picture when they figured out what I was doing.

The future of Mexico. Two little girls peer out of a second floor window, near where I had set up on the roof of the Secret Garden restaurant so I could get overhead shots of the parade. Mexico's children are its future, and it must have a big future because it has so many. These two were darling and immediately wanted me to take their picture when they figured out what I was doing.

This ends my posting on the Mexican Revolution and Ajijic's Dia de la Revolucion. Please feel free to comment in the comments area below. If you ask a question, please leave your email address in the comment box so that I can respond.

Hasta luego! Jim

Really enjoyed this! And realized how much I didn't know about the Mexican Revolution. And marvels of technology - immediately purchased a kindle book for night time reading about Pancho Villa exploits! And, of course, love your pictures!

ReplyDeleteYou outdid yourself! the clever combination of old and new photos was extremely well done.

ReplyDeleteKeep up the good work,

I always enjoy your photo-stories,

Julika

Great posting, Jim. I really like the way you've juxtaposed history and contemporary life. Thanks again for bringing your fresh perspective.

ReplyDeleteExcellent post! Don't know enough about the Mexican Revolution and this was a big help. Keep 'em coming...

ReplyDeleteGreat job. Reading your post took me back to my elementary school days in Mexico. Every child in Mexico is very aware and proud of his history. Jose

ReplyDeletehi could you please tell me where I can purchase a copy of the photo of pancho villa and Zapata entering san Cristobel on horse as this picture tells a story on its own and I would love to have a copy abbott336@btinternet.com .... yours frank

ReplyDeleteThe women in the white dress with Pancho Villa (his real name was Doroteo Arango Arambula) is Austreberta Renteria Ortega (b, 1894, d. 1982), Pancho Villa's third wife. (He also had dozens of partners before her.) She was my maternal grandfather's cousin. More specifically, Austreberta's father, Ignacio Renteria, was the brother of my great-grandfather.

ReplyDelete(He had 23 partners and three wives.)

ReplyDelete