Warriors gather in an Early Bronze age village. This scene captures life in Catalonia about 4000 years ago. While one warrior chats with a family, a metal worker prepares to pour molten bronze into molds. Another worker hammers the cooled axe heads into final shape. The warriors may be local men setting out on a mission or a passing detachment pausing to re-supply and catch up on the news. Warrior detachments often provided protection to merchant-traders who brought goods from as far away as the Baltic Coast or the Eastern Mediterranean. The men above are armed with bronze swords and spears tipped with bronze. They possess no protective armor other than simple bronze helmets and shields of hardened leather with bronze fittings.

Map of Iberian Peninsula during the Early Bronze Age. The Iberian Peninsula was usually one of the last areas of Europe to be reached by migrations and new pre-historic technologies. Copper was alloyed with arsenic to produce bronze in the Middle East as early as 7000 years ago. However, on the Peninsula, the Bronze Age began about 4200 years ago at El Argar , one of Europe's first state-level civilizations (see map). Bronze came to northeastern Iberia and Catalonia even later.

During this period, the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic (Copper Age) culture continued in Catalonia. The Bell Beaker phenomenon, which occurred late in the Chalcolithic period (see Part 4), is noted for its high quality copper and ceramic goods. However, little in the way of bronze was produced in Catalonia during this period and only on a small scale at scattered locations. Most bronze in use arrived through trade networks

One reason for the slow start of Catalonia's Bronze Age was the limited availability of tin. The discovery that tin was a much better alloy than arsenic led to more and better bronze, but tin was much more difficult to obtain. A look at the map above shows that most of the Iberian Peninsula's tin mines were located in the northwest, with only a handful in other areas and none in Catalonia.

The Bell Beaker/Steppe Culture in Catalonia

Ceramic pot in the Bell Beaker style. The pots were used for a wide variety of purposes, including as crucibles to melt metals such as copper, gold, and silver. These ceramics, as well as other features of the Bell Beaker phenomenon, were first produced for the elites in the Iberian Peninsula. They then spread through trade networks to other cultural elites in western and central Europe.

About 4500 years ago, just as the Bell Beaker phenomenon reached central Europe, the great migration of pastoralists from Eurasian steppes called the Yamnaya also reached that area (see Part 4). The high quality Bell Beaker artifacts and corresponding cultural ideas were quickly adopted by the newcomers. This probably helped them in their subsequent conquest of Europe's Neolithic/Chalcolithic cultures.

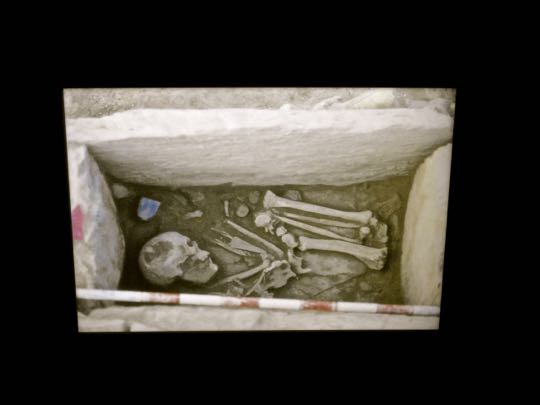

Yamnaya is Russian for "People of the pit burials". The Neolithic/Chalcolithic people had buried their dead in large communal barrows for thousands of years, reflecting their egalitarian heritage. By contrast, the pastoralists from the steppes, called the Yamnaya, usually buried their dead individually in stone lined pits called cists, and then covered these with mounds called kurgans. This method reflected the Yamnaya social hierarchy, based on chieftainship, patriarchy, and their concepts of personal property.

A striking feature of the Yamnaya was their great mobility and the key to this was their invention of wheeled vehicles. Their wagons were valued so highly that they were sometimes buried in kurgans with their owners. Mobility and a warlike attitude enabled them to rapidly take over the societies they encountered. This profound transformation can be seen in the Proto-Indo-European language the Yamnaya spoke, which became the basis for most modern European languages.

Over the centuries, waves of Yamnaya migrated into Europe, spearheaded by groups of young men who were seeking their fortunes in new areas. They mated with Neolithic/Chalcolithic women, to the detriment of Neolithic/Chalcolithic men whose DNA disappears from the genetic record in many areas at about the same time. All this led to dramatic cultural changes in many areas of Europe. However, as usual, such changes arrived much later in the Iberian Peninsula.

Daily life

Roundhouses were typical of many Early Bronze Age villages. The walls of roundhouses were a combination of wooden strips woven together and covered with mud. This method of construction is called "wattle and daub". The roofs were of thatched materials supported by wood poles. The large open room was heated by a fire pit in the center, where cooking activities also occurred. There was no chimney, since the smoke would filter out through the thatched materials.

The roundhouses provided both living and working areas for the multi-generational families who inhabited them. Weaving, potting, jewelry-making and other individual crafts would have been conducted inside, possibly by the light of the central fire.

Finely crafted shell necklace. People have been making jewelry from shells for at least 150,000 years. Various kinds of personal adornment found in the Early Bronze Age graves show that both sexes wore jewelry. This included items made from copper, bronze, gold, and silver, as well as shell necklaces like the one above.

To assemble this many individual shells, all of the same size and shape, and then shape and drill each of them so that they could be strung must have taken immense patience and concentration. It is not clear whether this particular necklace was made from shells collected from the Catalonian coast or whether the necklace arrived from elsewhere through the trade networks.

Unusual double vase found at Stiges, on the coast south of Barcelona. There is a nub of what may have been a handle on the part that connects the two containers. The purpose of the double vase is not clear and I could not find any other examples in Barcelona's Montjuic Museum of Archeology or on the internet.

Possibly it had some ceremonial function during feast rituals. It certainly would have been difficult to drink or pour from either vase without spilling from the other. I encourage anyone with any information or suggestions to share them.

Flanged axe head made during the Early to Middle Bronze Age. This axe was found at Cova d'Olopte, a cave north of Barcelona in the foothills of the Pyrenees Mountains. In the illustration at the beginning of this post, the two metal workers are creating flanged axes similar to this one.

Because of the dangerous and highly flammable nature of metallurgy, it would have been conducted outside the home, as seen in the first illustration. Axe heads like this may or may not have been intended for actual use as a tools. Sometimes they were used as ingots and melted down later to create other useful objects.

Early Bronze Age workman's tool kit. These artifacts are dated to between 4100 to 3500 years ago. They include a knife and a flat ax, both made of copper. The other knife and the punch are bronze made from an alloy of copper and arsenic.

Notice that neither of the knives has a tang, or shaft, to fit into a wood or bone handle. Instead, they have holes for rivets which would have attached them to their handles. These artifacts were found in various sites around Catalonia and are clearly intended as working tools rather than ingots.

Animal bones from the Early Bronze Age. These include large and small skulls, probably from domesticated animals like cattle and sheep. There are also two jaw bones, one from a canine and the other from a grazing animal, as well as a hollow leg bone. These remains may be the normal detritus of daily living. On the other hand, feasting was a popular way to commemorate religious or social occasions and to strengthen community bonds, as it still is today.

This completes Part 5 of my series on the ancient history of Barcelona and Catalonia. I hope you enjoyed it and, if so, you will include any thoughts or questions in the Comments section below or email me directly. If you leave a question, please include your email address so that I may respond in a timely manner.