Overview

This sunken area is the main courtyard. It lies two steps below the rest of the platform on which the overall compound is built. Carole is sitting on one of these steps in the upper right. In the upper left, you can see the entrance to the large room on the south side of the courtyard. The small, covered structure in the top center is roofed with modern corrugated materials to protect its murals. Many of the other rooms have similar coverings since none of Tepantitla's original roofs have survived. I found it curious that the courtyard lacks a central altar, unlike most of the main courtyards of other apartment compounds. Perhaps this area's main use was for communal activities by those living in the adjacent apartments. The steps to the temple platform can be seen in the center left.

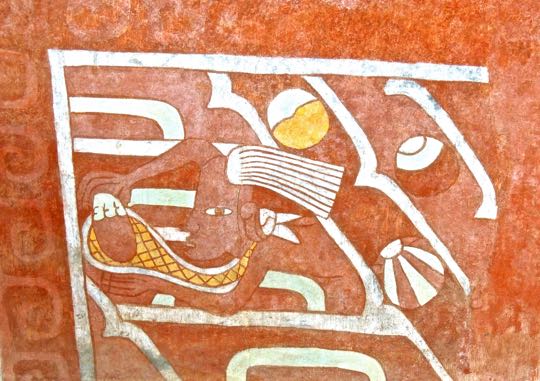

Room of the Marching Priests

A Sower-Priest in full regalia. The mural depicts a ritual offering during a ceremony aimed at ensuring a good crop. The priest wears the head and upper jaw of a crocodile, decorated with a plume of feathers. Crocodiles, in Mesoamerica, were associated with fertility and the arrival of rains. The priest's face is striped with horizontal bands of dark paint and he wears an elaborate costume that extends to his knees. In one of his hands, he holds a small satchel, marking him as a priest. The satchel probably contains copal incense. With the other hand, the priest sows seeds, another reference to fertility. A speech scroll extends in front of him but, unlike scrolls in other murals, this one emerges from his hand, not his mouth. The placement may relate to the seeds or the action of sowing, particularly since plants appear to be growing from the sides of the scroll and maiz (corn) and flowers can be seen within it.

Corner of the Room of the Marching Priests. The bands which frame the murals contain writhing Plumed Serpents. The head and twisting body of one serpent can be seen on the right, facing down. Water rushes from its mouth, further emphasizing the theme of fertility. The rattles within the band on the left identify the serpent as a rattlesnake. According to pre-hispanic myths, the Plumed Serpent (whom the Aztecs called Quetzalcoatl) gave the gift of maiz to humans and taught them how to cultivate and process it.

Mural of the Water Mountain

Mural of a mountain, gushing with water that is filled with swimmers. The mountain is surrounded by dancers and frolicking people. Archeologists have long debated the meaning of this mural. Initially, it was interpreted as Tlalocan, one of the 13 levels of heaven, ruled by Tlaloc, the Rain God. Tlalocan was a place of abundant water and never-ending springtime. The images seemed to fit Aztec beliefs about Tlaloc, but they arrived on the scene many centuries after Teotihuacán was abandoned. Many archeologists now believe that, rather than Tlalocan, this image represents Cerro Gordo, the extinct volcano that rises to the north of Teotihuacán, behind the Pyramid of the Moon. The mountain was revered by the Teotihuacanos as the source of their city's water. Current opinion now holds that the mural depicts Cerro Gordo as the sacred "Water Mountain", associated with the Great Goddess--Teotihuacán's chief deity--rather than Tlaloc.

Partying beside the Water Mountain. The mural contains scores of figures, not only in the water but on either side of the Water Mountain. Mixed in among them are flowering plants, butterflies and other creatures. A line of dancers can be seen in the upper center. Speech scrolls rise up from their mouths, indicating a song or chant. Each figure's left hand extends behind him between his legs and is grasped by the left hand of the following figure. Others dance individually or lie back languidly with their arms stretched out behind them. In the lower left, a man appears to towel himself off, with water dripping from his cloth. The overall impression is that there's one hell of a "pool party" going on.

Three figures feast on the fruit of a bush. Two of them reach out to grab the fruit, while the third bites it off directly from the bush. The scene is one of lushness and plenty.

Celebrating a good harvest. The men in this mural sing while marching along carrying poles on their shoulders. These may be agricultural implements. In some of the small fields near where I live, maiz is still planted by farmers using poles like this. One man looks back, with his speech scroll extending behind him. The other singing figure looks skyward and reaches his left hand upward in a gesture of joy. Below these two is a fragment of another singer, also with his head and hand raised. In this case, the hand holds an object that may be an offering.

Still more figures cavort and play. On the left, a group of men grasp the arms and legs of another man, preparing to playfully toss him in the air. Near them, a man trudges along, again with a speech scroll rising above his open mouth. Over his shoulder he carries a rolled up cloth (a beach towel?) with designs on it. Another dancer waves leafy branches. Oddly, I was unable to locate any women among the figures on the Water Mountain mural, although it is possible that some may have appeared in the missing sections. Also interesting is that these men do not appear to be priests, nobles, or members of the elite class. They are dressed as common folk and none are shown in the formal and rigid postures you find in elite depictions at Teotihuacán. The Water Mountain figures are in lively motion and the overall scene is one of joyful chaos.

The Great Goddess, Teotihuacán's chief deity, appears above the Water Mountain mural. This image is fragmentary, but you can see her huge feathered head dress with a bird head in the middle. She wears a dress adorned with floral symbols and her arms and wrists are circled with jade bracelets. As in other depictions of the Great Goddess, her arms are extended and water drips from her hands. Complete images of the Great Goddess (also known as the Jade Goddess) can be seen in my posting on Palacio Tetitla.

The Tlaloc Murals

The Rain God, later called Tlaloc by the Aztecs. On the left is the Rain God's face, wearing "goggles" around his eyes. Three arms can be seen to the right of the face, each holding vessels from which water gushes. Along the bottom is a rippled band representing a body of water. Within the band are a series of five-pointed stars which symbolize Venus. Venus is closely associated with the Rain God and fertility. It is the Evening Star which is reborn as the Morning Star each day. To pre-hispanic people, this represented the cyclical nature of the seasons and of death and rebirth. Along the top is a row of conch shell symbols, another aquatic theme. This mural is actually on the vertical part of a door frame, with the face at the bottom. I turned the photo so that you can better appreciate it.

The Red Tlalocs exhibit the fearsome side of the Rain God. The Red Tlalocs are part of a series that once decorated the whole wall of this room. Above the Tlalocs is a recurring series of single dots and double dashes. One interpretation is that the dots are circles representing chalchihuites (jewels). However, the numeric system used in pre-hispanic times gave values to dots and dashes: a dot equalled 1 and a dash equalled 5. If the symbols are numeric, it would show a series of elevens along the border of the mural. It is not clear which interpretation might be correct.

Artist's interpretation of the Red Tlalocs. Here you can see the images more clearly. The Rain God wears his typical goggles. Other typical features are a set of fangs and a drooping, forked tongue. His head dress contains obsidian knives and he carries an arrow bundle under his arm. These objects emphasize Tlaloc's scary aspects, expressed as thunder, lightning, terrible storms, and floods. Like many other gods, the Rain God could be fearsome as well as benevolent. He therefore required careful handling and regular propitiation through sacrifices, sometimes of the human variety.

Mural of the Red Shields

Despite its war-like name, the Mural of the Red Shields may not have a military meaning. The image gained its name from its resemblance to a chimali, or Aztec war shield. However, Teotihuacán war shields were square or rectangular, not round, so it is possible that the image has some other meaning besides a military one. If it does represent a warrior's shield, it may reflect the multi-cultural nature of Teotihuacán, which people from the Maya areas, the Zapotec kingdom of Monte Alban, as well as other parts of Mesoamerica.

Artist's rendering of the Red Shields. The central glyphs are surrounded by a band showing bird feathers. Inside the band is a glyph meaning Ojo de Reptil or "Reptile's Eye". It is possible that the combination of the reptile and feathers refers to the Plumed Serpent. The Ojo de Reptil glyph also appears on a stela at Xochicalco in the middle of a plaza that forms the entrance to that city. Archeologists believe that Xochicalco was founded by refugees from the collapse of Teotihuacán in 650 AD. Like Teotihuacan, images and references to the Plumed Serpent appear throughout Xochicalco.

Mural of the Four Petal Flowers

The image of a four-petal flower is ubiquitous at Teotihuacán. The sacred tunnel under the Pyramid of the Sun ends in chambers shaped like a four-petal flower. Four-petal flowers also appear in relief carvings on the columns at the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl, near the Pyramid of the Moon. There are many more examples to be found throughout the city. The four-petal flower symbolized the earth, with its four sacred directions. The designers of Teotihuacán divided the city into four quadrants, separated from north to south by the Avenue of the Dead. Another east to west avenue crossed the Avenue of the Dead perpendicularly at the Citadel. All this represented a conscious and deliberate attempt to build a city that imitated the cosmos with Teotihuacán at the center of the "four-petal" earth.

This completes my posting on Palacio Tepantitla. I hope you enjoyed the murals of this extraordinary compound. If you have any comments or questions, please leave them in the Comments section below, or email me directly.

If you leave a question in the Comments section, PLEASE leave your email address so that I can respond.

Hasta luego, Jim