The Jade Goddess is one of the stunning murals decorating the walls of the Palace of Tetitla. Like all the murals here, this one is painted on a red background of specular hematite, a pigment that includes tiny specks of mica. This gives it a subtle sparkle. The color red was associated with courage and was used on residences, temples and pyramids throughout Teotihuacán. The Jade Goddess is also referred to as the Great Goddess or the Spider Woman and she may have been the city's chief deity. Tetitla is one of five major palaces that have been discovered outside the perimeter of the main archeological site, although still well within the confines of the original ancient city. During our 2017 visit, we stopped by three of these sites, all of which contained spectacular murals. In this posting, I will focus on Tetitla.

Artist's conception of one of Tetitla's several courtyards as it looked in ancient times. A priest lays an offering on an altar while a nearby female sits reverently. The walls are vividly painted with murals and other symbols and the roof is decorated with pyramid-shaped almenas. Notice the rows of circles below the almenas and on the platform bases. These are called chachihuites, which represent something precious, such as water or jewels. Tetitla was built during the Tlamimilopan Phase (250-350 AD) of Teotihuacán's history and appears to have been occupied into the final Metepec Phase (650-750 AD).

Diagram of Tetitla's layout. It was an apartment compound for multiple families connected by kinship. The rooms are arranged around central, open-air patios that sometimes contain altars, like the one seen the artist's conception. The patios are set at levels below the surrounding rooms and contained drains that drew away rainwater that collected in them. The various individual compounds were connected by corridors.

One of the courtyards, as it looks today, with the remains of an altar/fire pit in the center. At its earliest stage, Tetitla was actually composed of two independent groups of structures. Over time, they spread out until they merged into the single architectural unit we see today. Tetitla was once surrounded by a high wall, with narrow roads separating it from other structures in the neighborhood. When we arrived, I got so involved with taking photos that I neglected to watch my step. Consequently, I tumbled off a platform and plunged into the corner of a wall, landing virtually at the feet of the security guard. As I lay stunned, he rushed to help me. Fortunately, I was not seriously hurt, although my arm and leg were bleeding freely from some pretty good nicks. The guard immediately retrieved his first aid kit and patched me up, as gently and skillfully as a trained nurse. I was glad he was there to help, but I felt pretty foolish. His assistance is typical of the Mexicans I have encountered when in need of help. Great people!

Ancient architectural sketches of two temples. Each shows staircases leading up to wide porticos with pillars in the entrances. The yellow-colored vertical rectangles are almenas. Teotihuacán's architects used sketches like this to design their buildings.

Model of a temple. Other methods used by the architects included models like this. This structure stands about 1.25 m (4 ft) tall and has a similar length in width at the base. The model is located in the middle of the largest patio and appears to have been used as an altar after its original purpose was served.

Room of the Nine Old Men. The mural at the base of the wall shows the profiles of nine old men, spread around the walls and all marching toward the back of the room. In the center of the back wall (left of photo) is another figure, facing front, but mostly obliterated. The room is square, roughly about 3.5 x 3.5 m (12 x 12 ft), and has a hard, stucco floor.

One of the Old Men. He is seen in profile with his arms crossed over his chest. The Old Man wears a cloth draped over his neck and carries a bag suspended between the two ends of the cloth. Archeologists speculate that the bag contains copal incense. The Old Man's ears are decorated by large jade ear plugs and speech balloons emerge from his mouth. Their shape indicates a flowery chant, perhaps in honor of the central figure he and the other eight Old Men are reverently approaching. The meaning of the ritual portrayed is just another of Teotihuacán's many mysteries.

Another patio, with four sets of stairs leading to separate rooms. The walls of the room at the far side of the patio contain another mural, this one related to Teotihuacan's near obsession with water and fertility.

Symbols representing water, fertility, and speech alternate along each wall. The curled pairs of symbols represent speech balloons emerging from a toothy mouth. The speech balloon may indicate a word, a chant or a prayer. Between each two pairs of speech balloons is another symbol showing two bivalve sea shells from which drops of water descend. Taken together, all this may represent a fervent prayer for regular rain and a good harvest.

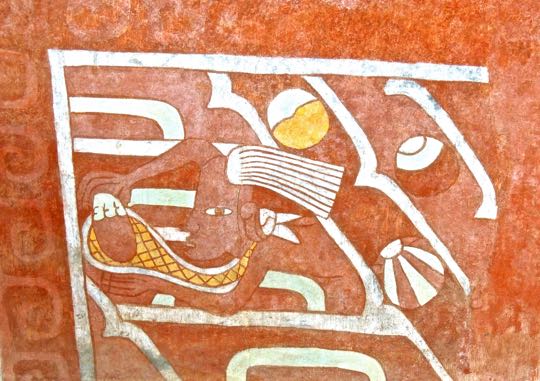

Diver putting a shell in a net. This is yet another water-related mural. In it a swimmer holds a shell in his right hand, preparing to place it in the net that is attached to his neck. The diagonal and horizontal white lines represent water ripples. This is one of the few murals at Tetitla that simulate movement. Behind the swimmer are three shells, one of them a scallop. Outside the white lines that border the swimmer are a series of symbols representing conch shells. While the mural illustrates Teotihuacán's focus on water, the seashells also highlight the importance of long-distance trade. Teotihuacán is located hundreds of miles from either the Gulf or Pacific Coasts.

A corridor is lined with rooms, including one with a bird and conch mural. The mural room, in the upper left, is connected both with the corridor and with the room to its right.

The Bird and Conch mural. The bird is shown in profile, perching on a conch shell trumpet. A speech balloon emerges from the trumpet's mouth, indicating a musical sound. There are two of these images on each wall, each facing another.

Room of the Eagles. This is a large square room with entrances from rooms on either side and one from the corridor. The fourth side contains an eagle with spread wings as well as several eagle heads. From the corridor entrance to the eagle mural, a sunken area runs the length of the room.

A fierce eagle spreads its wings. There has been some dispute about what sort of bird this represents. Both owls and quetzals have been suggested. However, zoologists have identified them as eagles. These were very powerful totems throughout Mesoamerican history. In fact eagles and jaguars were the totem animals of the two most important warrior cults in the later Toltec and Aztec empires. These eagles indicate a very high status family lived here, possibly including powerful military figures.

One of several eagle heads surrounding the bird with outstretched wings. The gaze is steady and piercing. Red drops pour from the beak, possibly indicating blood from a kill. This seems to reinforce the military interpretation.

Yet another corridor in the maze of rooms, patios, and courtyards. The layout is a bit confusing because there have been so many alterations over the 300-500 years of Tetitla's occupation.

These Jade Goddess murals are located in the patio with the temple model/altar. Her portraits also appear in other areas of Teotihuacán, including the Palace of Tepantitla (to be shown later) and the Jaguar Palace, as well as on ceramics. The archeological consensus is that she was the most important deity of this ancient civilization. This is another of Teotihuacán's many unusual aspects. The leading deities of all other major Mesoamerican civilizations were male, although goddesses often played subsidiary roles. The Jade Goddess was the deity of corn, earth, vegetation, and fertility. Although she was the paramount deity, she appears to have been a distant and somewhat ambivalent figure. As such, she would have provided a unifying structure for this multicultural city with its multiplicity of gods.

Artist's drawing of the Jade Goddess. The figure wears a lavishly feathered head dress which includes a bird's head, with what appears to be the twisting body of a serpent extending out from either side. The goddess' face is covered with a mask through which extend three fangs. Around her neck are several necklaces, including one with large, diamond-shaped jewels. The ears contain large jade spools. From the hands on the Jade Goddess' outstretched arms, water pours in two torrents. Contained within the water are various objects, including seeds, figurines, and shells. Conch symbols line the edges of the water streams. Her face mask, her jewelry, and the feathers and bird in her head dress are all green, a color which indicates water. Despite the fangs, the over impression is one of benevolence.

More narrow, twisting passageways. The colors and images on the corridor walls were too faded to make anything out, but clearly these were not neglected in decorating the palace. The twists and turn of the passageways continue the sense of wandering through a maze.

Dogs played an important part in life at Teotihuacán. Dogs, along with turkeys, were primary among the few domesticated animals in prehispanic times. These hairless and relatively small canines were called Xoloitzcuintli by the Aztecs. How the Teotihuacanos referred to them is unknown. Dogs were relished as a delicacy and were often served as a special dish at pre-hispanic weddings and funerals. In addition to food, the xoloitzcuintli played an important role in rituals related to death. Sacrificed dogs have been found in burial sites at Teotihuacán, as have ceramic pots in the shape of canines. The dog's role in the afterlife was to guide the dead into the underworld.

Felines were regarded as mystically powerful, particularly through their connection to the underworld. This feline is one of six found on the walls of a room. The elaborate head dress has long feathers and a headband that resembles a snake skin. This link to the sacred Plumed Serpent is probably not accidental. Dripping from the fanged mouth are bleeding hearts, the food of the gods. As night hunters, felines were believed to move between the worlds of the living and the dead. The bench on which the cat's belly rests has been interpreted as a kind of throne, indicating an especially high status. Because of their strength and predatory natures, felines were revered by warriors. Along with the murals of the eagles, the feline murals indicate the strong military connection of the family occupying the Tetitla Palace.

This completes my posting on the Palace of Tetitla. I hope you enjoyed it. Please leave any thoughts or questions in the Comments section below. If you leave a question, PLEASE leave your email address so that I can respond.

Hasta luego, Jim

Hi! That's a nice write-up on Teotihuacan. You know I have this comprehensive infographic on it (how to reach, best time to visit, etc.) which could really complement your post. Would you be interested reviewing it and featuring it on your blog?

ReplyDeleteBest,

Ravika

ravika.singh@practicebuzz.com

Thank you for the amazing photos and descriptions! Fantastic art, highly stylized and with lots of imbued meaning. I especially like the representations for speech. I haven't seen anything like it before.

ReplyDeleteDear Anonymous, thanks for your comment. Most people who visit Teotihuacan never see these murals because they only visit the big pyramids and the sites along the Avenue of the Dead. The murals can be seen both in the ruins of the ancient apartment buildings located in the areas immediately outside of the main site. Others can be seen in a small museum behind the Pyramid of the Moon, which is also seldom visited.

Delete