Cascada de San Pedro. This lovely curtain waterfall can be found on the edge of Zacatlán, at the head of one of the canyons leading into the vast Jilguero Gorge (see Part 1 of this series). The waterfall is about 20 meters (65 ft.) across and drops about 40 meters (130 ft.) into a rocky pool which leads to a torrent rushing down the gorge. In this part of my Zacatlán Odyssey series, we'll look at some of the ways past and present mingle seamlessly in Zacatlán. Photo by Mary Carmen Olvera Trejo.

Cascada de San Pedro. This lovely curtain waterfall can be found on the edge of Zacatlán, at the head of one of the canyons leading into the vast Jilguero Gorge (see Part 1 of this series). The waterfall is about 20 meters (65 ft.) across and drops about 40 meters (130 ft.) into a rocky pool which leads to a torrent rushing down the gorge. In this part of my Zacatlán Odyssey series, we'll look at some of the ways past and present mingle seamlessly in Zacatlán. Photo by Mary Carmen Olvera Trejo. Another view of Cascada de San Pedro. The quiet river winds through groves of trees past small farms, and then suddenly plunges vertically over a rocky ledge, beginning its long descent to the bottom of the gorge. The small park that surrounds the waterfall is easily reached and unfortunately, that is part of the problem. Mary Carmen, our hostess and guide, was Tourism Director until 2009. She worked with others in the community to put up rope safety barriers and place trash receptacles in the area. Now, the ropes were gone from their posts and empty pop bottles and other litter could be seen in the once pristine park. Fortunately, litter is the easiest form of pollution to clean up (think Gulf of Mexico). Still, Mary Carmen was angry and a little embarrassed that this lovely corner of her beloved Zacatlán had been a marred for her guests. Personally, I've seen much worse done to beautiful places in the US, so I wasn't unduly troubled. There are plenty of people in both countries that need a bit of consciousness raising, and cleaning up the park would only take a small crew an hour or so. But I understood her feeling.

Another view of Cascada de San Pedro. The quiet river winds through groves of trees past small farms, and then suddenly plunges vertically over a rocky ledge, beginning its long descent to the bottom of the gorge. The small park that surrounds the waterfall is easily reached and unfortunately, that is part of the problem. Mary Carmen, our hostess and guide, was Tourism Director until 2009. She worked with others in the community to put up rope safety barriers and place trash receptacles in the area. Now, the ropes were gone from their posts and empty pop bottles and other litter could be seen in the once pristine park. Fortunately, litter is the easiest form of pollution to clean up (think Gulf of Mexico). Still, Mary Carmen was angry and a little embarrassed that this lovely corner of her beloved Zacatlán had been a marred for her guests. Personally, I've seen much worse done to beautiful places in the US, so I wasn't unduly troubled. There are plenty of people in both countries that need a bit of consciousness raising, and cleaning up the park would only take a small crew an hour or so. But I understood her feeling. El Puente de San Pedro. The Bridge of San Pedro crosses the small river about 100 meters upstream from the falls. Mary Carmen didn't know the exact date when the bridge was built, but the style is that of the 19th Century. The road and stream crossing have been used for centuries, however. It is believed that the Zacateca tribe lived in the area around 583 AD. In 1115 AD, the Xólotl Chichimecas moved into the area and a series of their kings ruled Zacatlán, although they were vassals of the Aztecs at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

El Puente de San Pedro. The Bridge of San Pedro crosses the small river about 100 meters upstream from the falls. Mary Carmen didn't know the exact date when the bridge was built, but the style is that of the 19th Century. The road and stream crossing have been used for centuries, however. It is believed that the Zacateca tribe lived in the area around 583 AD. In 1115 AD, the Xólotl Chichimecas moved into the area and a series of their kings ruled Zacatlán, although they were vassals of the Aztecs at the time of the Spanish Conquest. Proud parents, out for an evening stroll. This pair of turkeys ambled along the bank of the river, keeping a watchful eye on several of their chicks racing around in every direction. Turkeys are native to the Americas, and were raised for food by the ancient indigenous people as early as 800 BC, as they still are today. The Spanish conquered the Aztecs in 1521, and the region around Zacatlán was granted to Hernán López de Avila as an "Encomienda," essentially a plantation served by indigenous slaves. Between 1522-1524, he removed the people from several outlying villages and settled them in the area of San Pedro Atmatla, not far from the falls, no doubt to keep them under his firm control. In 1562, they were moved again to the area that is now Zacatlán. For a map showing San Pedro Atmatla, the waterfall area, and their relation to Zacatlán, click here.

Proud parents, out for an evening stroll. This pair of turkeys ambled along the bank of the river, keeping a watchful eye on several of their chicks racing around in every direction. Turkeys are native to the Americas, and were raised for food by the ancient indigenous people as early as 800 BC, as they still are today. The Spanish conquered the Aztecs in 1521, and the region around Zacatlán was granted to Hernán López de Avila as an "Encomienda," essentially a plantation served by indigenous slaves. Between 1522-1524, he removed the people from several outlying villages and settled them in the area of San Pedro Atmatla, not far from the falls, no doubt to keep them under his firm control. In 1562, they were moved again to the area that is now Zacatlán. For a map showing San Pedro Atmatla, the waterfall area, and their relation to Zacatlán, click here.

Convent ruins evoke 1/2 millenium of history

Ruins of the Templo Franciscano. Horses grazed peacefully within the walls of the old Templo established by members of the Franciscan Order in the middle of the 16th Century. Unfortunately, a smallpox epidemic ravaged the community. The indigenous people had no immunity to European diseases and died by the hundreds, ultimately causing the abandonment of the old Templo. Between 1562-1567, the Franciscans constructed the current Templo and Convento de San Francisco, located on the plaza of Zacatlán (see Part 1). It is the fourth oldest church in Mexico. The ruins of its predecessor, the old Templo Franciscano, sit next to one of the few roads that wind down into the bowels of the great Jilguero Gorge.

Ruins of the Templo Franciscano. Horses grazed peacefully within the walls of the old Templo established by members of the Franciscan Order in the middle of the 16th Century. Unfortunately, a smallpox epidemic ravaged the community. The indigenous people had no immunity to European diseases and died by the hundreds, ultimately causing the abandonment of the old Templo. Between 1562-1567, the Franciscans constructed the current Templo and Convento de San Francisco, located on the plaza of Zacatlán (see Part 1). It is the fourth oldest church in Mexico. The ruins of its predecessor, the old Templo Franciscano, sit next to one of the few roads that wind down into the bowels of the great Jilguero Gorge. The ruins have been stabilized, but otherwise left untouched. Visited only by grazing horses and the occasional tourist, there were no signs or other information available on site. Fortunately, Mary Carmen proved to be a fountain of information, as usual. The only indication of the sacred nature of the ruins is the white cross painted in a small niche which can be seen on the back wall through the support timbers.

The ruins have been stabilized, but otherwise left untouched. Visited only by grazing horses and the occasional tourist, there were no signs or other information available on site. Fortunately, Mary Carmen proved to be a fountain of information, as usual. The only indication of the sacred nature of the ruins is the white cross painted in a small niche which can be seen on the back wall through the support timbers.  Window of the Templo looks out like the eye socket of an empty skull. Many different architectural styles can be found in Mexican buildings from the colonial era. However, convent architecture was dictated by the first Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza and his architect Toribio de Alcaraz. The style he chose is similar to that of churches built during and after the re-conquest of Spain from the Moors in the late Middle Ages, just before the Conquest of Mexico. When Mendoza turned over his responsibilities to his successor Don Luis Velasco in 1550, he left specific instructions regarding the construction of convents. The window above closely resembles those found in medieval castles and other defensive fortifications. This is not surprising, since the early colonial churches often became makeshift fortresses against indigenous uprisings. From the narrow slit, the window widens out in the thick walls to create a broad field of fire for the crossbowman or musketeer perched inside.

Window of the Templo looks out like the eye socket of an empty skull. Many different architectural styles can be found in Mexican buildings from the colonial era. However, convent architecture was dictated by the first Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza and his architect Toribio de Alcaraz. The style he chose is similar to that of churches built during and after the re-conquest of Spain from the Moors in the late Middle Ages, just before the Conquest of Mexico. When Mendoza turned over his responsibilities to his successor Don Luis Velasco in 1550, he left specific instructions regarding the construction of convents. The window above closely resembles those found in medieval castles and other defensive fortifications. This is not surprising, since the early colonial churches often became makeshift fortresses against indigenous uprisings. From the narrow slit, the window widens out in the thick walls to create a broad field of fire for the crossbowman or musketeer perched inside.

An old rancho connects the 18th with the 21st Century.

Rancho de Coyotepec, ancestral home of Mary Carmen's family. The Rancho was built sometime previous to 1791, the first date that appears in family records. In 1874, Mary Carmen's great-grandfather Don Juan Olvera y Manilla bought the rancho, and from then it has passed through the family from generation to generation. The walls are of adobe, and the roof of clay tiles. The two ancient wooden doors seen above lead into storage areas. The entrance is further to the right, through a archway over an old stone floor.

Rancho de Coyotepec, ancestral home of Mary Carmen's family. The Rancho was built sometime previous to 1791, the first date that appears in family records. In 1874, Mary Carmen's great-grandfather Don Juan Olvera y Manilla bought the rancho, and from then it has passed through the family from generation to generation. The walls are of adobe, and the roof of clay tiles. The two ancient wooden doors seen above lead into storage areas. The entrance is further to the right, through a archway over an old stone floor. The arched entranceway opens into a traditional courtyard, lush with gardens. Mary Carmen's sister, Rosy Olvera Trejo, and her sister's husband Vitor David Mendoza, emerge from the main house to greet us. Mary Carmen and Rosy are two of 8 sisters in the family. In addition, she has 3 brothers. Her father, the patriarch of the family, had died just the week before we visited. Later, we met her mother, a tiny woman. I was amazed that someone so small could have given birth to this huge brood. Presently, Rosy and Vitor live at Ranch de Coyotepec, while the rest of the family live elsewhere in Zacatlán.

The arched entranceway opens into a traditional courtyard, lush with gardens. Mary Carmen's sister, Rosy Olvera Trejo, and her sister's husband Vitor David Mendoza, emerge from the main house to greet us. Mary Carmen and Rosy are two of 8 sisters in the family. In addition, she has 3 brothers. Her father, the patriarch of the family, had died just the week before we visited. Later, we met her mother, a tiny woman. I was amazed that someone so small could have given birth to this huge brood. Presently, Rosy and Vitor live at Ranch de Coyotepec, while the rest of the family live elsewhere in Zacatlán.  Rustic outside, roomy and comfortable inside. We settled down in this inviting living room for tea and conversation. Vitor pulled out a photo album and began to detail the family history to me. Although he spoke only in Spanish, and my skills in that language are still pretty iffy, to my surprise we were able to understand one another very well. The walls of the room were filled with old family momentos and pictures going far back into the 19th Century. Rosy and Vitor not only live at Rancho de Coyotepec, but they run it as a bed and breakfast and spa called Tonantzin Spa Hostal. Rosy is a trained masseuse with a salon off the courtyard. To access the Tonantzin website, click here.

Rustic outside, roomy and comfortable inside. We settled down in this inviting living room for tea and conversation. Vitor pulled out a photo album and began to detail the family history to me. Although he spoke only in Spanish, and my skills in that language are still pretty iffy, to my surprise we were able to understand one another very well. The walls of the room were filled with old family momentos and pictures going far back into the 19th Century. Rosy and Vitor not only live at Rancho de Coyotepec, but they run it as a bed and breakfast and spa called Tonantzin Spa Hostal. Rosy is a trained masseuse with a salon off the courtyard. To access the Tonantzin website, click here. Ceiling decorations confirm the antiquity of the home. Looking up in the living room, I marveled at these old-fashioned ceiling decorations. The rafters cross over one another forming square boxes which were painted ages ago with scrollwork and animal figures.

Ceiling decorations confirm the antiquity of the home. Looking up in the living room, I marveled at these old-fashioned ceiling decorations. The rafters cross over one another forming square boxes which were painted ages ago with scrollwork and animal figures. An inviting kitchen. I have an affection for big kitchens. As a boy I spent a lot of time hanging out in ours as my Mom prepared meals and we discussed the affairs of the world. Rosy's kitchen was not only functional, but tiled colorfully and appeared just the place to spend a long morning dawdling over coffee. My guess is that her clients make a bee-line for her kitchen when they enter the main house. It's that kind of place.

An inviting kitchen. I have an affection for big kitchens. As a boy I spent a lot of time hanging out in ours as my Mom prepared meals and we discussed the affairs of the world. Rosy's kitchen was not only functional, but tiled colorfully and appeared just the place to spend a long morning dawdling over coffee. My guess is that her clients make a bee-line for her kitchen when they enter the main house. It's that kind of place. An ancient hedge of unknown origin. No one in the family knows who originally planted these hedges, only that they have always been here, just outside the kitchen door. It may well be that they were planted in the 1700's when the house was built, since such hedges were popular in that time period.

An ancient hedge of unknown origin. No one in the family knows who originally planted these hedges, only that they have always been here, just outside the kitchen door. It may well be that they were planted in the 1700's when the house was built, since such hedges were popular in that time period. A lover's walk? Leading back from the house, which can be seen peeping through the trees, the walkway loops through a large pasture before returning to the house. It struck me as an ideal route for a young couple in love, under the watchful eyes of parents and grandparents, of course. I later remarked to Mary Carmen that meeting and learning about her family was like entering a different world. My life experience has involved living all over the US, with a little time in Asia. I have no deep sense of place or roots. My extended family lives all over the world. I was fascinated by such a large family with such deep roots in one place, and whose occupation of the ancestral home goes back almost 150 years.

A lover's walk? Leading back from the house, which can be seen peeping through the trees, the walkway loops through a large pasture before returning to the house. It struck me as an ideal route for a young couple in love, under the watchful eyes of parents and grandparents, of course. I later remarked to Mary Carmen that meeting and learning about her family was like entering a different world. My life experience has involved living all over the US, with a little time in Asia. I have no deep sense of place or roots. My extended family lives all over the world. I was fascinated by such a large family with such deep roots in one place, and whose occupation of the ancestral home goes back almost 150 years.

Jicolapa, city with a legend

Jicolapa's legend dates back to the 17th Century. This little town of less than 2000 people lies just outside Zacatlán, and is part of its municipality. Jicoplapa means, in Nahuatl, "the place where the Jicotes live." For a map showing Jicolapa in relation to Zacatlán, click here. In 1675, school children noticed an apparition on the adobe walls of their school, located on the plaza. Although they tried repeatedly to erase the obscure design, it continued to return, becoming clearer each time. It finally revealed itself as the image of Jesus Christ. The children brought their teachers and parents to view it, and all agreed it was marvelous. Word spread to outlying pueblos and more people came to marvel and pay their respects, bringing flowers and incense and other gifts. Some people claimed to have been healed of their infirmities by their visit, and the fame of the image increased even more.

Jicolapa's legend dates back to the 17th Century. This little town of less than 2000 people lies just outside Zacatlán, and is part of its municipality. Jicoplapa means, in Nahuatl, "the place where the Jicotes live." For a map showing Jicolapa in relation to Zacatlán, click here. In 1675, school children noticed an apparition on the adobe walls of their school, located on the plaza. Although they tried repeatedly to erase the obscure design, it continued to return, becoming clearer each time. It finally revealed itself as the image of Jesus Christ. The children brought their teachers and parents to view it, and all agreed it was marvelous. Word spread to outlying pueblos and more people came to marvel and pay their respects, bringing flowers and incense and other gifts. Some people claimed to have been healed of their infirmities by their visit, and the fame of the image increased even more. A sorrowful Virgin Mary occupies a niche in the Iglesia del Señor de Jicolapa. There were numerous saints in other niches, but I was attracted by this simple, sorrowful figure. For more than a century the old school survived as an hermitage. Priests began saying Mass at the shrine. For many years the shrine at the school was cared for by an old lady, but then the school caught fire one day. Miraculously, the image was spared the damage of the flames. Eventually the church seen above was built at the site to protect and celebrate the miraculous image. People still come to pay homage each February.

A sorrowful Virgin Mary occupies a niche in the Iglesia del Señor de Jicolapa. There were numerous saints in other niches, but I was attracted by this simple, sorrowful figure. For more than a century the old school survived as an hermitage. Priests began saying Mass at the shrine. For many years the shrine at the school was cared for by an old lady, but then the school caught fire one day. Miraculously, the image was spared the damage of the flames. Eventually the church seen above was built at the site to protect and celebrate the miraculous image. People still come to pay homage each February. Jicolapa's plaza is neat, colorful, and tidy. Above, a stroller passes two lovers kissing by the stairs to the kiosco. The little town has the feeling of arrested time.

Jicolapa's plaza is neat, colorful, and tidy. Above, a stroller passes two lovers kissing by the stairs to the kiosco. The little town has the feeling of arrested time.  The store with no name...because it doesn't need one. Mary Carmen tells me that stores in little pueblos like Jicolapa are often unnamed because they have been there so long and are so well known. Why would anyone bother? This nameless tienda sits right on the corner of the plaza, a short distance from the kiosco and the church.

The store with no name...because it doesn't need one. Mary Carmen tells me that stores in little pueblos like Jicolapa are often unnamed because they have been there so long and are so well known. Why would anyone bother? This nameless tienda sits right on the corner of the plaza, a short distance from the kiosco and the church.  Inside the store, Mary Carmen chats with a friend. The woman behind the counter is Guadalupe Cabrera López. She was obviously happy to see Mary Carmen, and curious about us. Christopher and I leaned on the ancient wooden counter and took in the feel of a place from another century.

Inside the store, Mary Carmen chats with a friend. The woman behind the counter is Guadalupe Cabrera López. She was obviously happy to see Mary Carmen, and curious about us. Christopher and I leaned on the ancient wooden counter and took in the feel of a place from another century. How about a little "snort" of something to take the chill off? While the store sold a variety of goods, one of the most popular seemed to be homemade liquers, concocted from local fruits and herbs. Sra. Guadalupe pulled a bottle of green liquid off the shelf and doled out a couple of small shots. I don't drink alcohol normally, but politeness and curiosity won the day. It tasted something quite like creme de menthe, but the bottle was unmarked, as were all of them on the shelf. While we were sampling and chatting, a young Mexican man came in and secured a bottle for himself and a friend, both of them sipping from the bag-covered bottle as they surveyed the plaza from the steps of the "no name" store.

How about a little "snort" of something to take the chill off? While the store sold a variety of goods, one of the most popular seemed to be homemade liquers, concocted from local fruits and herbs. Sra. Guadalupe pulled a bottle of green liquid off the shelf and doled out a couple of small shots. I don't drink alcohol normally, but politeness and curiosity won the day. It tasted something quite like creme de menthe, but the bottle was unmarked, as were all of them on the shelf. While we were sampling and chatting, a young Mexican man came in and secured a bottle for himself and a friend, both of them sipping from the bag-covered bottle as they surveyed the plaza from the steps of the "no name" store.  Mexican humor. While savoring my taste of the green stuff, I noticed this sign above the counter. A rough translation is "the only ones trusted by us are those more than 90 years old, accompanied by their little grandmother." I suspected this meant they wouldn't take my personal check on an out-of-country bank.

Mexican humor. While savoring my taste of the green stuff, I noticed this sign above the counter. A rough translation is "the only ones trusted by us are those more than 90 years old, accompanied by their little grandmother." I suspected this meant they wouldn't take my personal check on an out-of-country bank.

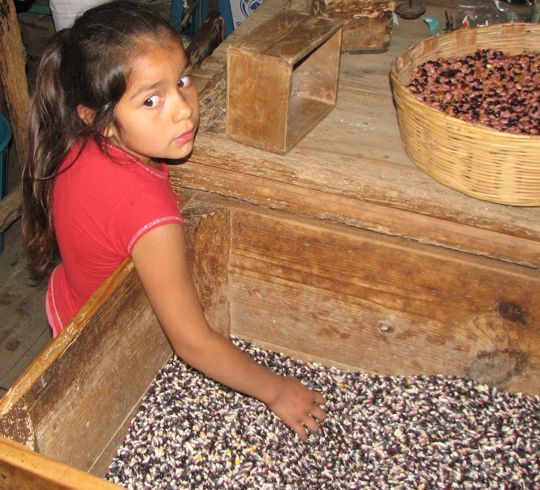

María, trying to disguise her curiosity. This little girl hung about, running her fingers through the beans in the bin, obviously trying to eves drop on the conversations, even the ones in English she probably didn't understand. Since neither Christopher nor I ever saw another Norteamericano during our visit at Zacatlán, we must have provoked intense curiousity and speculation, particularly among children who have a harder time disguising their feelings. Sometimes, from their expressions, I felt a bit like a space alien.

A relic of the past in another old store. Another unnamed store across the street was owned by a woman named Lucila Alvarez. When she spotted Mary Carmen, she invited us in to inspect this old fountain in the interior courtyard of what, in its time, may have been an elegant old home. On the side of the fountain, I found a plaque with the date "25 Dec 1888." Mexicans seem to love flowers, and the old courtyard was almost overwhelmed by Sra. Lucila's plants.

A relic of the past in another old store. Another unnamed store across the street was owned by a woman named Lucila Alvarez. When she spotted Mary Carmen, she invited us in to inspect this old fountain in the interior courtyard of what, in its time, may have been an elegant old home. On the side of the fountain, I found a plaque with the date "25 Dec 1888." Mexicans seem to love flowers, and the old courtyard was almost overwhelmed by Sra. Lucila's plants. The bird that named a gorge. Above, a Jilguero (Brown-backed Solitaire) inspects its visitors in the old courtyard with the fountain. These birds swarm in the lush forests of the gorges around Zacatlán, giving the one just below the city its name Barranca del Jilguero, or Jilguero Gorge.

The bird that named a gorge. Above, a Jilguero (Brown-backed Solitaire) inspects its visitors in the old courtyard with the fountain. These birds swarm in the lush forests of the gorges around Zacatlán, giving the one just below the city its name Barranca del Jilguero, or Jilguero Gorge.

This completes Part 3 of my Zacatlán Odyssey series. Next week we'll go on a trip through ruggedly beautiful mountains to visit remote indigenous villages. Stay tuned! If you would like to leave a comment, you can either do so in the comments section below, or email me directly. If you choose to leave a questions in the comments section PLEASE leave your email address so that I can respond.

Hasta luego, Jim