In this posting, I will show some of the grave goods recovered from four ancient cemeteries: El Embocadero II, Los Coamajales, El Pantano, and Los Tanques. These sites represent some of the earliest examples of the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition. The first section will focus on sculptures of people and animals. The second will show various ceramic vessels and discuss their possible uses. The final section will display various tools and items of household use. Altogether, these artifacts create a window into the far-distant past. Throughout the posting, I will provide information about the Capacha Culture which produced these artifacts, as well as some insight into the archeological techniques used to interpret these specific finds.

Dr. Joseph Mountjoy led the archeological work at the four cemeteries. Above, he carefully removes dirt from the surface of a pot unearthed at a tomb in the El Pantano site. Dr. Mountjoy is an expert on the ancient sites in this part of Mexico. He has published two papers on these particular cemeteries, including "Excavation of two Middle Formative Cemeteries in the Mascota Valley", and "From the living to the dead: connecting the ceramic figures with the people of the shaft and chamber tomb culture." Most of the information I present here came from these papers. They were invaluable in helping me understand the people who lived in the Mascota Valley 2800 years ago. When my information comes from other sources, I will provide a link. (Photo by Nick Corduan in Pinterest)

Sculptures of people and animals

Pairs of male and female statues have been found in several of the tombs. All of the tombs containing the pairs were located in El Pantano cemetery. According to Mountjoy, the pairs represent two deities, Father Sun and Mother Earth. Another interpretation is that they represent the "Original Pair" who came together to produce humans, a sort of pre-hispanic Adam and Eve.

You may notice some significant differences between these figures and the seated man seen previously. Unlike the relaxed, natural posture of the seated man, the two above are very formal and stylized. These differences in style separate the human figures found in the tombs into two groups. The natural figures tend to be seated, in various relaxed postures. In contrast, the stylized ones all stand erect, with their feet apart, their shoulders slightly hunched, and their hands clasping their stomachs. Why the two groups are so different is something I have yet to determine.

However, the human figures also possess similarities. Figures representing gods are found in both groups. All of the figures, natural or stylized, have narrow, squinting eyes, tiny mouths, and all are nude, or nearly so. In almost every case, gender can be determined by the small, high-set breasts of the females and the substantial genitalia of the males. An exception to this is an androgynous figure, with no overt sexual characteristics. It was found buried with a high status child whose bones were so deteriorated that the child's gender could not be determined.

This cheerful little dog with a striped coat was found in El Pantano cemetery. I couldn't help smiling when I saw it. It looks as if it is chuckling at an amusing joke. Pre-hispanic people kept dogs both as pets and for food. The presence of ceramic dogs in the tombs is significant. The dogs provide evidence that, even at this early date, people viewed dogs as guides and companions for the journey into the death. When the Spanish arrived, almost 2300 years later, the Aztecs were worshipping Xolotl, a dog-god whose role was to guide the dead through the perils of the underworld. While most of the dog sculptures found in the tombs are hollow containers, this one is solid.

The contents of the tombs tell us a good deal about the Capacha Culture as it existed in the Mascota Valley. There was some social differentiation, but nothing like the highly stratified societies found in other areas of Mesoamerica. Social status in the Mascota Valley was fairly fluid and a man could rise above a humble beginning. The Capacha built no great cities, nor did they construct pyramids, temples, or palaces. Village populations in the Mascota Valley ranged in size from 100 to 500 people. The economy was based primarily on the cultivation of corn and beans and the hunting of wild animals, particularly deer and turtles.

This seated figure embodies aspects of two gods who later became very important. The holes across the face are for the insertion of hair to create a beard. This connects the figure to the bearded god who taught humans about corn. In later eras, he was called Quetzacoatl (Feathered Serpent). The grooves on the neck, chest and legs suggest flaying, which is the process of cutting and peeling human skin. This is a link to the "Flayed God" who was later known as Xipe Totec. Both Quetzalcoatl and Xipe Totec are related to fertility and the cycle of the seasons. Rather than sitting on the ground, the figure is seated on a bench, a position of power.

Because the Capacha Culture never developed monumental architecture, there is minimal above-ground evidence of their presence. Our understanding of the culture comes overwhelmingly from the contents of the shaft tombs. Unfortunately, a great deal of information has been lost because many tombs have been looted, including some within the four cemeteries of the Mascota Valley. However, other tombs have been discovered intact and, even in the looted areas, some grave goods and bones have been recovered.

A dog with a man's face. Sculptures like this are called anthropomorphic, because they display both animal and human features. The body is that of a long-necked dog, but the face has the narrowly slitted eyes and tiny mouth found on the human statues. The statue is a hollow container and the top of the head is open, forming the spout. While the sculptures can tell us a lot about culture, social status and religious beliefs, the bones also provide an important trove of information.

Osteoarcheology is the study of ancient skeletons. From their bones we can tell a lot about the physique of the people, their lifestyle, diet, ailments, lifespan, and sometimes the cause of death. Analysis of the teeth can reveal whether they were well-fed or malnourished as children, an indication of the social status of their parents. Teeth can also reveal whether the people lived their lives near where they were buried or came from some distant location. That, in turn, tells us whether the community was isolated or connected into the larger world of its time.

Woman sitting with an infant in her lap. This is another of the relaxed-posture human sculptures. She sits on the ground with one leg resting across the other, while cradling her baby against her right arm. Her face seems calm and serene, unlike the glum expressions of the women with the dead infants seen in Mascota, Part 2.

Like the other hollow dogs, this one has a spout at the top of its head. The figure conveys a sense of energy and impending movement, as if the dog is gathering itself to leap into someone's lap. As with the long-necked dog, the face of this one resembles those of the human figures.

A crying woman with tattoos. She stands in the same posture as the other statues in the stylized group. The dots on her face represent tattooing, an indication of social status. Below the dots are four slanted lines, two on either side of the nose. On another statue, Mountjoy describes similar lines as tears.

Possible predecessor of the famous Colima Dogs? This chubby little creature resembles the "Colima Dogs" found in shaft tombs near the city of Colima. However, this statue pre-dates them by a thousand years. The much-later Colima Dogs are more finely crafted and do not have anthropomorphic faces.

Ceramic containers

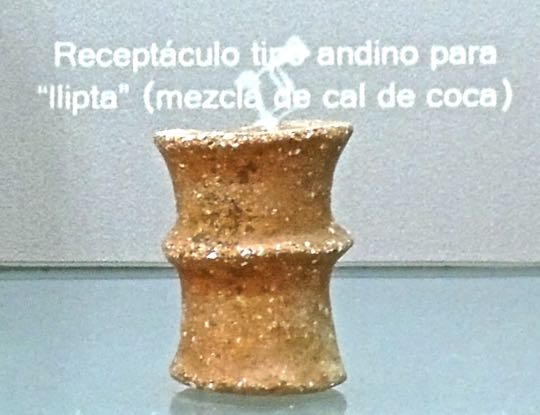

A "snuff/lime dipping vessel" found in a looted area of Los Coamajales. The vessel is about the size of a shot glass. It had been discarded by looters who considered it worthless. To the archeologists who retrieved it, the vessel was an important find. Similar vessels have been found at Capacha sites near Apulco in western Jalisco and El Opeño in Michoacan. The vessels at all three sites have, in turn, been linked to similar vessels found in Peru. This helps confirm the existence of very early trade route between western Mexico's Capacha Culture and South America's ancient Pacific Coast civilizations. Among these was the Andean culture known as the Chavin.

Los Coamajales cemetery was in use from around 1000 BC to 800 BC. In the Peruvian Andes, at that time, the Chavin Culture (900-200 BC), was also developing. The Chavin liked to snort llipta, a kind of snuff made from lime and ground-up coca leaves. They crafted small snuff containers, similar to the Capacha vessel seen above, to hold the snuff.

The Chavin lived on the slopes of South America's Andes, the natural habitat of the coca plant, and llipta may have been a very distant ancestor of cocaine. Chavin priests or shamans used llipta ritually, in order to put themselves into an hallucinatory state. It is possible that this vessel arrived in the Mascota Valley along the trade routes from Peru, but it is more likely a Capacha copy. In addition to vessels like this, it is likely that coca leaves made the same journey from the Peruvian Andes.

A "water-cover pot" is actually two pots in one. The mouth of the larger pot is covered with the base of the smaller one. This appears to produce a steaming process when it is used. Although a sign near the pot mentioned the cooking of frijol (beans), I have since discovered a different possibility. While Googling for this posing, I came across a research article about the possibility of alcohol distillation in the pre-hispanic Americas. This is a controversial issue. It has long been believed that pre-hispanic people never developed an alcohol distillation process, although they did ferment agave to produce the mildly alcoholic drink called pulque.

The researchers, who are called "experimental archeologists", used reproductions of Capacha-style pottery of various kinds to see if they could distill alcohol with them. They were careful to use only the techniques and materials that would have been available in western Mexico at that time. These included fermented agave and Capacha-style ceramics, including water-cover pots, crafted by Mexican potters using locally-obtained clay. After much experimentation, the researchers succeeded in producing ethanol containing distillates. While this doesn't conclusively prove the case, it certainly establishes that alcohol distillation was possible at that early time and provides a basis for further research.

Long-necked pottery in the shape of a gourd. The earliest containers used by archaic hunter-gatherers were made from materials such as hollowed-out squashes and gourds. Since they moved around constantly, and had no draft animals (at least in North America), everything they carried had to be light. However, once people settled down in farming communities, clay pottery came into use. It makes sense that their ceramics would mimic the shapes of the light-weight containers used by their wandering predecessors.

"Stirrup spout" bottles like this provide another connection to the Chavin Culture of South America. The bottle gets its name from its similarity to the stirrup attached to European saddles. Since I was unable to find mention of this piece of pottery in Dr. Mountjoy's excavation report on El Embocadero II and Los Coamajales, it must have been recovered from a shaft tomb at either El Pantano or Los Tanques. Stirrup spout bottles have been found in Chavin Culture sites, once again connecting the Capacha settlements of the Mascota Valley with Northwestern South America.

These containers would have been difficult to make and therefore expensive. It is likely that they would have been the prized possessions of elite figures in the community. Archeologists believe they were not used for household purposes. Instead, their probable use was for religious rituals and funerary rites. Outside of the El Pantano shaft tombs, no bottles of this sort have been found anywhere else in the Mascota Valley. In fact, when similar bottles were discovered in the Chavin context, nearly all came from tombs. Had they been intended for common household use, many would have been found in residential contexts, but almost none were.

Ceramic pot made in the shape of a squash. A pot that may well be the same was found in a shaft tomb at El Embocadero II. This is the tomb from which the statue of the sitting man (first photo) was recovered. You can see a photo of the tomb in my Mascota Part 2 posting. This is another example of how the traditional gourds and squashes were largely supplanted by ceramic pottery when people adopted a sedentary lifestyle.

There are several reasons for this. Pottery fashioned from clay can be given specialized shapes to suit a wide variety of needs. With natural gourds and squash, you must use what you can find. In addition, ceramic containers hold water well and can be used over a cooking fire. Further, they offer much more protection from rodents and micro-organisms. Since sedentary people are not moving around constantly, the weight of the pots and their relative fragility are of much less concern.

A pot with a colander? I was fascinated by this pot and its possible uses. The upper part has a series of holes of various sizes that are aligned in a precise, geometric order. Could this be an ancient colander, used to strain water from cooked food? Was it another part of the alcohol distillation process? Whatever its purpose, this device certainly seems sophisticated for a stone-age people living 2800 years ago.

I was also intrigued by the pattern of the holes, which suggest the four Sacred Cardinal Directions. The lip of the pot has been damaged. This may have been from a collapse of the tomb chamber's roof. On the other hand, it might reflect the practice of "killing" a piece of pottery so that it could enter the underworld with its dead owner. In fact, deliberate breakage has occurred with other ceramics found in the cemeteries.

Decorations on Capacha ceramics often include incised markings. The parallel grooves are an example of this sort of decoration. The purpose of the four pairs of knobs is less clear. However, they could have been used to hold cords in place if the pot was intended to hang from the ceiling. This was a common practice to prevent rodents, insects, and wayward children from getting into the contents. The ability to add knobs and other features to a container is another example of the usefulness of ceramic pots, as opposed to hollowed out gourds or squashes.

Tools and household items

Obsidian spear points were used to tip an atlatl dart. Obsidian is volcanic glass which is easily chipped into tools or weapons, as well as jewelry. The edge of an obsidian flake can be sharper than a surgical scalpel. Consequently, volcanic glass was an extremely valuable resource to pre-hispanic people. The Mascota Valley has many sites where it can be obtained. In addition to local use, obsidian was an important trade item. Those with ready access could exchange it for valuable goods brought from other areas.

"Atlatl" is a Nahuatl word, from the language of the Aztecs. An atlatl is a device used to propel a dart or short spear with much greater force than can be obtained with the throwing arm alone. It is a Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) technology, dating back at least 17,000 years. To use it, the dart is propelled forward from the atlatl handle, using an overhand motion. To understand this action, go to any large park. There, you will find someone throwing a ball to his dog using a flexible plastic rod about 46cm (18in) long with a cup at the end to hold the ball. This is the same technology used by people 17,000 years ago to propel their darts.

Dugout canoe. This ancient dugout would have been used to travel on rivers and lakes in the area in order to fish or transport goods. Dugout canoes are one of the earliest methods of water transportation and are still used by remote tribes today. Such a boat only requires a tree trunk of the correct diameter, cut the desired length.

Using stone tools, a groove was cut along one side of the trunk. Fire embers were placed in the groove to slowly burn away the wood of the interior. Using their stone tools, the craftsmen gradually cut away the burned wood until the interior was hollowed out. The prow of this particular boat was originally shaped in the form of an eagle. The dugout was found at Laguna de Juanacatlán, a lake not far from the town of Mascota.

Mano and metate, essential tools of the pre-hispanic kitchen. The mano is the oval grinding stone on top of the four-legged stone tray, called the metate. Similar devices were used by the pre-agricultural Paleolithic people to grind the wild seeds they gathered. Of course, once corn was domesticated around 8,700 years ago, the mano and metate became essential for grinding the corn kernels into masa, or dough, from which the first tortillas were made. Metates can still be found in Mexican hardware stores. They are not sold as tourist trinkets, but for use in Mexican kitchens.

Ancient turtle shell. Turtle meat was an important part of the diet of the people in the Mascota Valley. They had local access to freshwater turtles, but could also hunt sea turtles on the Pacific Coast, only 82km (51mi) away. From its size, this is probably an ancient sea turtle shell.. In addition to consuming the meat, pre-hispanic people used the shell as a percussion musical instrument.

This completes Part 3 of my Mascota series. I hope you have enjoyed it. If so, please leave any thoughts or questions in the Comments section below or email me directly. If you leave a question in the Comments section, PLEASE leave your email address so that I can respond.

Hasta luego, Jim