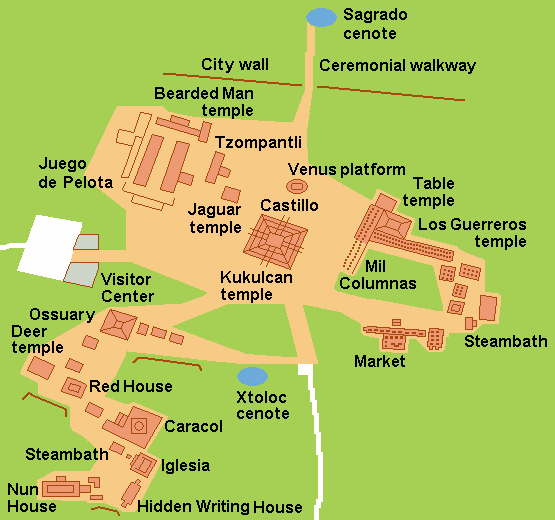

A fierce snake bares its fangs on the Temple of Warriors. At the top step of Temple of Warriors, a pair of snakes representing Kukulcan, also known as Quezalcoatl the Feathered Serpent, stand on either side of a grand staircase. On top of the snakes' heads are small Atlantean Toltec warriors who once held banners. This temple was apparently a key structure related to the warrior societies which conquered and ruled Chichen Itza. They included the Eagles and Jaguars. In this second part of my Chichen Itza series, we will look at the Temple of Warriors, the Court of a Thousand Columns, the Market, the Observatory, the living quarters of common people, and the site called the Nunnery. You can see a site map by clicking here.

A fierce snake bares its fangs on the Temple of Warriors. At the top step of Temple of Warriors, a pair of snakes representing Kukulcan, also known as Quezalcoatl the Feathered Serpent, stand on either side of a grand staircase. On top of the snakes' heads are small Atlantean Toltec warriors who once held banners. This temple was apparently a key structure related to the warrior societies which conquered and ruled Chichen Itza. They included the Eagles and Jaguars. In this second part of my Chichen Itza series, we will look at the Temple of Warriors, the Court of a Thousand Columns, the Market, the Observatory, the living quarters of common people, and the site called the Nunnery. You can see a site map by clicking here. Front view of the Temple of Warriors. The Temple stands a short distance away from El Castillo also known as the Pyramid of Kukulcan, and across the central plaza from the Ball Court and its associated structures such as the Tzompantli (Platform of Skulls) and the Jaguar Platform. All of these structures glorify warriors and warfare and are associated with human sacrifice. The people who built The Temple of Warriors and other buildings of the great plaza were not the peaceful stargazers they were thought to be a few decades ago. At the top of the staircase of the Temple of Warriors, a Chacmool gazes out over the wide plaza. Chacmools are stone-carved human figures reclining on their backs, while leaning on their elbows. On their stomachs are bowls carved into the stone which may have been receptacles for still-beating human hearts cut out of living chests with sharp obsidian blades. The Temple of Warriors is a bigger, grander, version of Temple B found at the Toltec capital of Tollan north of present-day Mexico City. I have visited both temples in the ruined cities and the resemblance is startling. The relationship between these two cities is still a matter of conjecture.

Front view of the Temple of Warriors. The Temple stands a short distance away from El Castillo also known as the Pyramid of Kukulcan, and across the central plaza from the Ball Court and its associated structures such as the Tzompantli (Platform of Skulls) and the Jaguar Platform. All of these structures glorify warriors and warfare and are associated with human sacrifice. The people who built The Temple of Warriors and other buildings of the great plaza were not the peaceful stargazers they were thought to be a few decades ago. At the top of the staircase of the Temple of Warriors, a Chacmool gazes out over the wide plaza. Chacmools are stone-carved human figures reclining on their backs, while leaning on their elbows. On their stomachs are bowls carved into the stone which may have been receptacles for still-beating human hearts cut out of living chests with sharp obsidian blades. The Temple of Warriors is a bigger, grander, version of Temple B found at the Toltec capital of Tollan north of present-day Mexico City. I have visited both temples in the ruined cities and the resemblance is startling. The relationship between these two cities is still a matter of conjecture. On the south end of the Temple of Warriors is the Court of a Thousand Columns. While there aren't really 1000, there are at least several hundred. The columns stand in several parallel rows surrounding most of a large plaza area, as well as running the length of the front of the Temple of Warriors. At one time they were roofed, but the covering has long since fallen. The use of such columns to support roofs and separate rooms was an innovation of the ruling warrior class who may have taken over the already ancient Maya city around 800 AD. The previous style, called Puuc, used few if any columns. At the base of the steps leading up to the columns is another open-mouthed snake.

On the south end of the Temple of Warriors is the Court of a Thousand Columns. While there aren't really 1000, there are at least several hundred. The columns stand in several parallel rows surrounding most of a large plaza area, as well as running the length of the front of the Temple of Warriors. At one time they were roofed, but the covering has long since fallen. The use of such columns to support roofs and separate rooms was an innovation of the ruling warrior class who may have taken over the already ancient Maya city around 800 AD. The previous style, called Puuc, used few if any columns. At the base of the steps leading up to the columns is another open-mouthed snake. North Colonnade looking south. This colonnade runs north to south along the front of the Temple of Warriors (see picture #2 above). Most of these columns had tumbled to the ground centuries ago, but in 1926 Carnegie Institution restored their grandeur, along with many of the other great structures of Chichen Itza.

North Colonnade looking south. This colonnade runs north to south along the front of the Temple of Warriors (see picture #2 above). Most of these columns had tumbled to the ground centuries ago, but in 1926 Carnegie Institution restored their grandeur, along with many of the other great structures of Chichen Itza. Many of the columns on the south side are square and carved with reliefs. Toltec warriors, grim faced and armored, look back at us across the centuries.

Many of the columns on the south side are square and carved with reliefs. Toltec warriors, grim faced and armored, look back at us across the centuries. The rulers of Chichen Itza were not only warriors, but merchants. On the south side of the Court of a Thousand Columns is the Market, a structure that must have been splendid in its own right. Above you can see the broad staircase leading into the Market area. There is evidence that merchants and artisans transported their wares here from as far away as Tikal in Guatamala.

The rulers of Chichen Itza were not only warriors, but merchants. On the south side of the Court of a Thousand Columns is the Market, a structure that must have been splendid in its own right. Above you can see the broad staircase leading into the Market area. There is evidence that merchants and artisans transported their wares here from as far away as Tikal in Guatamala. Slender columns line the sunken quadrangle of the Market. I could imagine hundreds of people milling here, examining various wares such as bird feathers, carved wood, shells from the coast, jade and obsidian, and cotton cloth. The Toltecs were skilled artisans and their name means "artificers" or "those that make things".

Slender columns line the sunken quadrangle of the Market. I could imagine hundreds of people milling here, examining various wares such as bird feathers, carved wood, shells from the coast, jade and obsidian, and cotton cloth. The Toltecs were skilled artisans and their name means "artificers" or "those that make things".  Feathered warrior in a stone relief found in the Market area. I found the concept of "warrior-merchants" an odd one, until I remembered the fur trappers of the American Northwest. They also were great fighters as well as tradesmen.

Feathered warrior in a stone relief found in the Market area. I found the concept of "warrior-merchants" an odd one, until I remembered the fur trappers of the American Northwest. They also were great fighters as well as tradesmen. The elite of Chichen Itza also contained great astronomers. The building above is called the Observatory. It also gained the nickname Caracol, which is Spanish for snail. The cylindrical ruins do somewhat resemble a snail shell on end. The building is related to Quetzalcoatl, but shows strong elements of the previous Puuc style, which indicates it may have been constructed during the rule of the Maya priests, before the coming of the warrior cults.

The elite of Chichen Itza also contained great astronomers. The building above is called the Observatory. It also gained the nickname Caracol, which is Spanish for snail. The cylindrical ruins do somewhat resemble a snail shell on end. The building is related to Quetzalcoatl, but shows strong elements of the previous Puuc style, which indicates it may have been constructed during the rule of the Maya priests, before the coming of the warrior cults. It is called the Observatory for a reason. You can see from the design above what the building may have originally looked like. Many of the openings in the upper, cylindrical structure align with the sun, Venus, or other astronomical features. From the observations made by the astronomer-priests, predictions could be made for practical purposes such as when to plant crops, as well as for mystical religious reasons.

It is called the Observatory for a reason. You can see from the design above what the building may have originally looked like. Many of the openings in the upper, cylindrical structure align with the sun, Venus, or other astronomical features. From the observations made by the astronomer-priests, predictions could be made for practical purposes such as when to plant crops, as well as for mystical religious reasons. How the common people lived. Of course, the people who lived in and around Chichen Itza were not just the warriors and priestly elite. The Maya commoners tilled the land and performed all the services the elite needed and wanted. They lived in snug huts called chozas in Spanish or nah in Maya, like the reconstruction shown above. The roof is thatched and the walls are made of upright posts plastered with mud. On the facade of the South Building of the Nunnery in Uxmal are stone carvings of nah exactly like the one shown above.

How the common people lived. Of course, the people who lived in and around Chichen Itza were not just the warriors and priestly elite. The Maya commoners tilled the land and performed all the services the elite needed and wanted. They lived in snug huts called chozas in Spanish or nah in Maya, like the reconstruction shown above. The roof is thatched and the walls are made of upright posts plastered with mud. On the facade of the South Building of the Nunnery in Uxmal are stone carvings of nah exactly like the one shown above. Interior of the choza. The choza is actually quite roomy inside. Forked posts with cross pieces hold the roof in place. It is high-peaked so that even a tall norteamericano like me could walk around comfortably. As our bus made its way through the back roads of the Yucatán State, we saw people living in structures identical to this, sometimes with a small satellite dish on top. 8th Century AD meets the 21st Century!

Interior of the choza. The choza is actually quite roomy inside. Forked posts with cross pieces hold the roof in place. It is high-peaked so that even a tall norteamericano like me could walk around comfortably. As our bus made its way through the back roads of the Yucatán State, we saw people living in structures identical to this, sometimes with a small satellite dish on top. 8th Century AD meets the 21st Century!  The Nunnery complex contains a two-story structure called the Church. The Spanish had no frame of reference but their own to understand and name the ancient ruins they found. The Church and an adjacent ruin called the Nunnery appeared to the Spanish to resemble the convents they remembered from Spain. Religion may have be practiced here, but it was far from anything known in Spain. The style of this part of Chichen is clearly Puuc, and this seems to be the oldest part of the city. Notice the "roof comb" on top of the Church. This sort of stone lattice work was very popular in Puuc structures, but is absent in the buildings constructed after the warriors took over.

The Nunnery complex contains a two-story structure called the Church. The Spanish had no frame of reference but their own to understand and name the ancient ruins they found. The Church and an adjacent ruin called the Nunnery appeared to the Spanish to resemble the convents they remembered from Spain. Religion may have be practiced here, but it was far from anything known in Spain. The style of this part of Chichen is clearly Puuc, and this seems to be the oldest part of the city. Notice the "roof comb" on top of the Church. This sort of stone lattice work was very popular in Puuc structures, but is absent in the buildings constructed after the warriors took over. Profile of Chaac, the rain god. Masks of Chaac, with the long elephant-like trunk and bared teeth are another typical element of Puuc style. Chaac is not to be confused with the Chacmool, which was introduced by the Toltec. In the Yucatán rainfall is very uncertain, so Chaac was an important deity.

Profile of Chaac, the rain god. Masks of Chaac, with the long elephant-like trunk and bared teeth are another typical element of Puuc style. Chaac is not to be confused with the Chacmool, which was introduced by the Toltec. In the Yucatán rainfall is very uncertain, so Chaac was an important deity. Part of the Nunnery complex, next to the Church. Puuc buildings were typically two story, with intricate geometic designs on the stone facade, and Chaac masks on the corners.

Part of the Nunnery complex, next to the Church. Puuc buildings were typically two story, with intricate geometic designs on the stone facade, and Chaac masks on the corners.  Detail from the Nunnery building. A figure with crossed arms and legs, richly adorned with a feathered head dress, sits over the doorway. This may be a representation of a high priest or other elite figure. Interestingly, the entire front of the building forms a giant Chaac mask. The figure above forms the nose and the door below is the mouth.

Detail from the Nunnery building. A figure with crossed arms and legs, richly adorned with a feathered head dress, sits over the doorway. This may be a representation of a high priest or other elite figure. Interestingly, the entire front of the building forms a giant Chaac mask. The figure above forms the nose and the door below is the mouth. The Ossuary, or High Priests Grave. Along a forest trail, we suddenly encountered this small pyramid called the Ossuary. Although smaller than El Castillo, it too has nine levels, which correspond to the nine levels of the Maya underworld. It is a cross-over building, with Puuc-style Chaac masks, as well as Kukulcan snake heads at the bottom of the staircases.

The Ossuary, or High Priests Grave. Along a forest trail, we suddenly encountered this small pyramid called the Ossuary. Although smaller than El Castillo, it too has nine levels, which correspond to the nine levels of the Maya underworld. It is a cross-over building, with Puuc-style Chaac masks, as well as Kukulcan snake heads at the bottom of the staircases. What the Ossuary may have looked like originally. Missing today is the temple on top. An opening inside the temple leads down into a limestone cave complex that goes on for miles. The Ossuary is part of the complex of structures which relate to the Xtoloc Cenote, the main water supply for Chichen Itza. This pyramid pulls it all together: Kulkulcan, Chaac, the reverence for water and cenotes, and the mystical significance of caves in Maya religion.

What the Ossuary may have looked like originally. Missing today is the temple on top. An opening inside the temple leads down into a limestone cave complex that goes on for miles. The Ossuary is part of the complex of structures which relate to the Xtoloc Cenote, the main water supply for Chichen Itza. This pyramid pulls it all together: Kulkulcan, Chaac, the reverence for water and cenotes, and the mystical significance of caves in Maya religion. After our visit to Chichen Itza, we lunched at the Hacienda Chichen. This beautiful old hacienda was owned by Spanish and later Mexican aristocrats who gave scant thought to the great ruins in their back yard. Some of the structures of the hacienda were built with stones taken from Chichen Itza.

After our visit to Chichen Itza, we lunched at the Hacienda Chichen. This beautiful old hacienda was owned by Spanish and later Mexican aristocrats who gave scant thought to the great ruins in their back yard. Some of the structures of the hacienda were built with stones taken from Chichen Itza. Ruins of the old gate house at Hacienda Chichen. Founded as early as 1523, the hacienda is the oldest in Yucatán and one of the oldest in Mexico. The main economic activity was cattle-raising.

Ruins of the old gate house at Hacienda Chichen. Founded as early as 1523, the hacienda is the oldest in Yucatán and one of the oldest in Mexico. The main economic activity was cattle-raising.  Well at Hacienda Chichen. The main hacienda house, called the Casco was built near the permanent well or Noria so as to control the water supply of the area, and therefore the Maya.

Well at Hacienda Chichen. The main hacienda house, called the Casco was built near the permanent well or Noria so as to control the water supply of the area, and therefore the Maya. The Hacienda Chichen became an early base for archaeologists. Sylvanus Morley (1883-1948) may have been the model for the Indiana Jones character of the movies. US Consul Edward Thompson (1856-1935) actually purchased the Hacienda Chichen and the ruins it contained so he could pursue his interest in archaeology. He spirited some of his finds out of the country to museums in the US, causing an uproar. They were finally returned, many years later. Many other important archaeologists stayed here in later years. In the 1930s a Mexican family bought the hacienda and its ruins from the Thompson family and turned it into an elegant hotel for those visiting Chichen Itza.

The Hacienda Chichen became an early base for archaeologists. Sylvanus Morley (1883-1948) may have been the model for the Indiana Jones character of the movies. US Consul Edward Thompson (1856-1935) actually purchased the Hacienda Chichen and the ruins it contained so he could pursue his interest in archaeology. He spirited some of his finds out of the country to museums in the US, causing an uproar. They were finally returned, many years later. Many other important archaeologists stayed here in later years. In the 1930s a Mexican family bought the hacienda and its ruins from the Thompson family and turned it into an elegant hotel for those visiting Chichen Itza.

This completes Part 2 of my 2-part series on Chichen Itza. It's massive popularity detracts a bit from the serenity I like in ancient ruins, but I suppose that is inevitable given its close proximity to an international resort like Cancun. Still, it is definitely worth a visit by anyone interested in Mexico's ancient heritage. There are few sites as impressive. If you would like to leave a comment, please use the Comments section below or email me directly. If you leave a question in the Comments section, PLEASE leave your email address so that I can respond.

Hasta luego, Jim